10.2 General assessment and management guidelines

Decline in vision is associated with normal ageing and is therefore an important consideration for fitness to drive in the general care of older people, along with consideration of cognition and sensory-motor function (refer to Part A section 2.2.7. Older drivers and age- related changes).

Progressive eye conditions such as cataracts, glaucoma and macular degeneration are also more common in older people. Once diagnosed, these conditions require regular monitoring in relation to driving, including through conditional licences as appropriate (refer to section 10.2.4. Progressive eye conditions). Regular monitoring is also required for conditions such as diabetes to screen for and manage end-organ effects (retinopathy) (refer to section 3.2.3. Comorbidities and end-organ complications).

For drivers with neurological conditions such as stroke, vision is one of a number of functional outcomes that will be addressed as part of an overall assessment of fitness to drive, and findings will need to be integrated as part of this overall assessment (refer to section 6.3. Other neurological and neurodevelopmental conditions).

In this section

10.2.4. Progressive eye conditions

10.2.5. Congenital and acquired nystagmus

10.2.7. Orthokeratology therapy

10.2.8. Telescopic lenses (bioptic telescopes)

10.2.9. Practical driver assessments

10.2.1 Visual acuity

For the purposes of this publication, visual acuity is defined as a person’s clarity of vision with or without glasses or contact lenses. Where a person does not meet the visual acuity standard at initial assessment, they may be referred for further assessment by an optometrist or ophthalmologist.

Assessment method

Visual acuity should be measured for each eye separately and without optical correction. If optical correction is needed, vision should be retested with appropriate corrective lenses. For use of orthokeratology lenses to correct visual acuity, refer to section 10.2.7. Orthokeratology therapy.

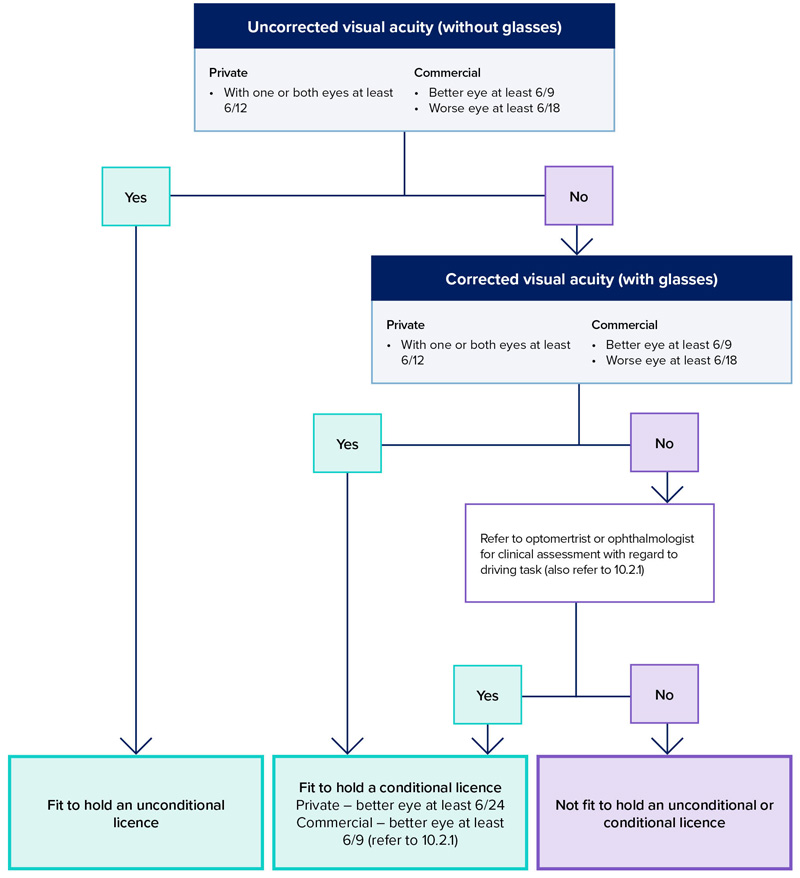

Acuity should be tested using a standard visual acuity chart (Snellen or LogMAR chart or equivalent) with five letters on the 6/12 line. Standard charts should be placed six metres from the person tested; otherwise, a reverse chart can be used and viewed through a mirror from a distance of three metres. Other calibrated charts can be used at a minimum distance of three metres. More than two errors in reading the letters of any line is regarded as a failure to read that line. Refer to Figure 17 for a management flow chart.

In the case of a private vehicle driver, if the person’s visual acuity is just below that required by the standard but the person is otherwise alert, has normal reaction times and good physical coordination, an optometrist or ophthalmologist can recommend the granting of a conditional licence. The use of contrast sensitivity or other specialised tests may help in the assessment. However, a driver licence will not be issued when visual acuity in the better eye is worse than 6/24 for private vehicle drivers.

There is also some flexibility for commercial vehicle drivers depending on the driving task, providing the visual acuity in the driver’s better eye (with or without corrective lenses) is 6/9 or better. Restrictions on driving (conditional licence) may be advised; for example, where glare is a marked problem, no-night driving may be recommended. Refer to Part A section 4.4. Conditional licences.

Figure 17: Visual acuity requirements for private and commercial vehicle drivers

10.2.2 Visual fields

For the purposes of this publication, visual fields are defined as a measure of the extent of peripheral (side) vision. Normal visual field is: 60 degrees nasally, 100 degrees temporally, 75 degrees inferiorly and 60 degrees superiorly. The binocular field extends the horizontal extent from 160 to 200 degrees, with the central 120 degrees overlapping and providing the potential for stereopsis.

Visual fields may be reduced due to a range of neurological conditions (e.g. stroke, multiple sclerosis) as well by ocular diseases (e.g. glaucoma), or injuries, resulting in hemionopia, quadrantanopia or monocularity.

Peripheral vision assists the driver to be aware of the total driving environment. Once alerted, the central fovea area is moved to identify the importance of the information. Therefore, peripheral vision loss that is incomplete will still allow awareness; this includes small areas of loss and patchy loss. Additionally, affected drivers can adapt to the defect by scanning regularly and effectively and can have good awareness. Patients with visual field defects who have full intellectual/cognitive capacity are more able to adapt, but those with such impairments will have decreased awareness and are therefore not safe to drive.

A longstanding field defect, such as from childhood, may lead to visual adaptation. Such defects need to be assessed by an optometrist or ophthalmologist for a conditional licence to be considered. They should be managed as an exceptional case to the standard, with consideration for duration and evidence of visual adaptation, whether the location of the defect is an area that may already be blocked by the car door on the passenger side (i.e. the inferior field on the left side without central field loss), driver safety record and the nature of the driving task.

Assessment method

If there is no clinical indication of a visual field impairment or a progressive eye condition, then it is satisfactory to screen for defect by confrontation. Confrontation is an inexact test. Any person who has, or is suspected of having, a visual field defect should have a formal perimetry-based assessment.

Monocular automated static perimetry is the minimum baseline standard for visual field assessments. If monocular automated static perimetry shows no visual field defect, this information is sufficient to confirm that the standard is met.

Subjects with any significant field defect or a progressive eye condition require a binocular Esterman visual field for assessment. This is classically done on a Humphrey visual field analyser, but any machine that can be shown to be equivalent is accepted (e.g. Medmont binocular VF printed off in level map mode). The treating optometrist or ophthalmologist can determine whether it is appropriate for the person to wear their normal corrective lenses while undergoing testing. Fixation monitoring must be performed and recorded on the test. Alternative devices must have the ability to monitor fixation and to stimulate the same spots as the standard binocular Esterman. For an Esterman binocular chart to be considered reliable for licensing, the false-positive score must be no more than 20 per cent.

Horizontal extent of the visual field

In the case of a private vehicle driver, if the horizontal extension of a person’s visual fields are less than 110 degrees but greater or equal to 90 degrees, an optometrist or ophthalmologist may support the granting of a conditional licence by the driver licensing authority. The extent is measured on the Esterman from the last seen point to the next seen point. There is no flexibility in this regard for commercial vehicle drivers.

A single cluster of up to three adjoining missed points, unattached to any other area of defect, lying on or across the horizontal meridian will be disregarded when assessing the horizontal extension of the visual field. A vertical defect of only a single point width but of any length, unattached to any other area of defect, that touches or cuts through the horizontal meridian may be disregarded. There should be no significant defect in the binocular field that encroaches within 20 degrees of fixation above or below the horizontal meridian. This means that homonymous or bitemporal defects that come close to fixation, whether hemianopic or quadrantanopic, are not normally accepted as safe for driving.

Central field loss

Scattered single missed points or a single cluster of up to three adjoining points is acceptable central field loss for a person to hold an unconditional licence. A significant or unacceptable central field loss is defined as any of the following:

- a cluster of four or more adjoining points that is either completely or partly within the central 20-degree area

- loss consisting of both a single cluster of three adjoining missed points up to and including 20 degrees from fixation, and any additional separate missed point(s) within the central 20-degree area

- any central loss that is an extension of a hemianopia or quadrantanopia of size greater than three missed points.

Methods of measuring visual fields are limited in their ability to resemble the demands of the real- world driving environment where drivers are free to move their eyes as required and must sustain their visual function in variable conditions. Additional factors to be considered by the driver licensing authority in assessing patients with defects in visual fields therefore include, but are not limited to, the following:

- kinetic fields conducted on a Goldman

- binocular Esterman visual fields conducted without fixation monitoring, often referred to as a roving Esterman (two consecutive tests must be performed with no more than one false-positive allowed) – the test should be in the numeric field format when it is printed out or sent for an opinion

- contrast sensitivity and glare susceptibility

- medical history; duration and prognosis; if the condition is progressive; rate of progression/deterioration; effectiveness of treatment/management

- driving record before and since the occurrence of the defect

- the nature of the driving task – for example, type of vehicle (truck, bus, etc.), roads

- and distances to be travelled concomitant medical conditions such as cognitive impairment or impaired rotation of the neck.

There is no flexibility in this regard for commercial vehicle drivers.

Monocular vision (one-eyed driver)

Monocular drivers have a reduction of visual fields due to the nose obstructing the medial visual field. They also have no stereoscopic vision and may have other deficits in visual functions.

For private vehicle drivers, a conditional licence may be considered by the driver licensing authority if the horizontal visual field is 110 degrees and the visual acuity is satisfactory in the better eye. People with monocular vision are generally not fit to drive a commercial vehicle. A conditional licence may be considered by the driver licensing authority if the horizontal visual field is 140 degrees, the visual acuity in the better eye is satisfactory, there is no other visual field loss that is likely to impede driving and an ophthalmologist/optometrist assesses that the person may be safe to drive after consideration of the above factors. The better eye must be reviewed at least every two years.

If monocular automated static perimetry is undertaken on patients without symptoms, family history or risk factors for visual field loss, and shows no indication of any visual field concerns, this information may be sufficient to confirm that the standard is met. If monocular testing suggests a field defect, or if the patient has a progressive eye condition, and/or the patient has any other symptoms or signs that indicate a field defect, then binocular testing should be conducted using the Esterman binocular field test or an Esterman-equivalent test. Alternative devices must have the ability to monitor fixation and to stimulate the same spots as the standard binocular Esterman.

Sudden loss of unilateral vision

A person who has lost an eye or most of the vision in an eye on a long-term basis has to adapt to their new visual circumstances and re-establish depth perception. They should therefore be advised not to drive for an appropriate period after the onset of their sudden loss of vision (usually three months). They should notify the driver licensing authority and be assessed according to the relevant visual field standard.

10.2.3 Diplopia

People suffering from all but minor forms of diplopia are generally not fit to drive. Any person who reports or is suspected of experiencing diplopia within 20 degrees from central fixation should be referred for assessment by an optometrist or ophthalmologist. For diplopia managed with an occluder, a three-month non-driving period applies in order to re-establish depth perception.

10.2.4 Progressive eye conditions

The patient should be advised appropriately when a progressive eye condition is diagnosed that may result in future restrictions on driving. It is important to give the patient as much lead time as possible to prepare for changes that may later be required (e.g. adaptation to alternate transport and/or engaging blindness and low vision services). Refer to Part A section 2.2.6. Congenital conditions, disability and driving and 2.2.7. Older drivers and age-related changes.

People with progressive eye conditions such as cataract, glaucoma, optic neuropathy, diabetic retinopathy, macular degeneration or retinitis pigmentosa should be monitored regularly and should be advised in advance about the potential future impact on their driving ability.

10.2.5 Congenital and acquired nystagmus

Nystagmus may reduce visual acuity. Drivers with nystagmus must meet the visual acuity standard. Any underlying condition must be fully assessed to ensure there is no other issue that relates to fitness to drive. Those who have congenital nystagmus may have developed coping strategies that are compatible with safe driving and should be individually assessed by an appropriate specialist.

10.2.6 Colour vision

There is not a colour vision standard for drivers, either private or commercial. Doctors, optometrists and ophthalmologist should, however, advise drivers who have a significant colour vision deficiency about how this may affect their responsiveness to signal lights and the need to adapt their driving accordingly. Note, this standard applies only to driving within normal road rules and conditions. A standard requiring colour vision may be justified based on risk assessment for particular driving tasks.

10.2.7 Orthokeratology therapy

See reference 14

Orthokeratology involves the therapeutic use of rigid gas-permeable contact lenses worn overnight to reshape the cornea of the eye. This provides effective correction of visual refractive error (once the lenses are removed) that can last at least a full day. The therapeutic effect is temporary and so the lenses must be worn regularly to maintain the best visual outcomes.

A conditional licence can be considered for private and commercial vehicle drivers provided the visual acuity standard is met with orthokeratology therapy and the lenses are worn as recommended by an optometrist or ophthalmologist. The driver may drive without their normal correcting lenses (e.g. glasses or contact lens) provided that the visual acuity standard is maintained with the support of orthokeratology therapy. If the driver cannot meet or maintain the standard using orthokeratology therapy, they must drive with correcting lenses that enable them to meet the standard.

10.2.8 Telescopic lenses (bioptic telescopes)

The driver licensing authority may refuse a licence if the visual acuity standards are not met without the use of a bioptic telescope (refer to section 10.2.1. Visual acuity). People seeking to use a bioptic device for driving should first contact their driver licensing authority and check whether these devices are an accepted means to meet the standards. Refer to Appendix 9 for driver licensing authority contact details.

Bioptic telescopes are devices used to compensate for reduced visual acuity. They are miniature telescopes typically mounted on the upper part of a person’s glasses. Bioptics are used momentarily and intermittently when driving, the majority of which occurs at the corrected visual acuity provided by the person’s glasses. The person drops their chin slightly to view through the telescope for magnification, then lifts their chin to view through their standard corrective lens.

At present, there is insufficient information from human factors and safety research of drivers using these devices to set standards for bioptics. As such, and due to the increased risk associated with commercial vehicle driving (refer to Part A section 4.1. Medical standards for private and commercial vehicle drivers), these devices should not be used to meet the visual acuity standards for commercial vehicles. For private vehicle drivers, the driver licensing authority may consider information from an assessment performed by an ophthalmologist or optometrist when making its licensing decision.

10.2.9 Practical driver assessments

A practical driver assessment is not considered to be a safe or reliable method of assessing the effects of disorders of vision on driving, especially the visual fields, because the driver’s response to emergency situations or various environmental conditions cannot be determined. Information about adaptation to visual field defects can be gained from visual field tests such as the Esterman.

A practical driver assessment may be helpful in assessing the ability to process visual information (refer to Part A section 2.3.1. Practical driver assessments).

10.2.10 Exceptional cases

In unusual circumstances, cases may be referred by the driver licensing authority for further medical specialist opinion (refer to Part A section 3.3.7. Role of independent experts/panels).