8.2 General assessment and management guidelines

8.2.1 General considerations

Excessive daytime sleepiness, which manifests itself as a tendency to doze at inappropriate times when intending to stay awake, can arise from many causes and is associated with an increased risk of motor vehicle crashes. It is important to distinguish sleepiness (the tendency to fall asleep) from fatigue or tiredness that is not associated with a tendency to fall asleep. Many chronic illnesses cause fatigue without increased sleepiness.

Increased sleepiness during the daytime in otherwise normal people may be due to prior sleep deprivation (restricting the time for sleep), poor sleep hygiene habits, irregular sleep– wake schedules or the influence of sedative medications, including alcohol. Insufficient sleep (less than five hours) prior to driving is strongly related to motor vehicle crash risk. Excessive daytime sleepiness may also result from a range of medical sleep disorders including the sleep apnoea syndromes (OSA, central sleep apnoea and nocturnal hypoventilation), periodic limb movement disorder, circadian rhythm disturbances (e.g. advanced or delayed sleep phase syndrome), some forms of insomnia and narcolepsy.

Unexplained episodes of ‘sleepiness’ may also require consideration of the several causes of blackouts (refer to section 1. Blackouts).

8.2.2 Identifying and managing people at high crash risk

Until the disorder is investigated, treated effectively and licence status determined, people should be advised to avoid or limit driving if they are sleepy, and not to drive if they are at high risk, particularly in the case of commercial vehicle drivers. High-risk people include:

- those who experience moderate to severe excessive daytime sleepiness

- those with a history of frequent self-reported sleepiness while driving

- those who have had a motor vehicle crash caused by inattention or sleepiness.

People with these high-risk features have a significantly increased risk of sleepiness-related motor vehicle crashes. These people should be referred to a sleep disorders specialist, particularly in the case of commercial vehicle drivers. Driving limitations may include avoiding driving at night and after consuming alcohol or sedative drugs, and limiting continuous driving (e.g. to between 15 minutes and two hours depending on symptoms) until effective treatment is implemented (refer to section 8.2.5. Advice to patients).8

8.2.3 Sleep apnoea

Definitions and prevalence

Diagnosed sleep apnoea has been reported in 8.3 per cent of Australian adults, 12.9 per cent of men and 3.7 per cent of women. Approximately 3 per cent of adults have diagnosed sleep apnoea and excessive daytime sleepiness, indicating a significant tendency to doze off in various situations during the daytime, including when driving. Sleep apnoea syndrome (excessive daytime sleepiness in combination with sleep apnoea on overnight monitoring) is present in 2 per cent of women and 4 per cent of men. Some studies suggest a higher prevalence in transport drivers.

OSA involves repetitive obstruction to the upper airway during sleep, caused by relaxation of the dilator muscles of the pharynx and tongue and/ or narrowing of the upper airway, resulting in cessation (apnoea) or reduction (hypopnoea) of breathing.

Central sleep apnoea refers to a similar pattern of cyclic apnoea or hypopnoeas caused by oscillating instability of respiratory neural drive, and not due to upper airways factors. This condition is less common than OSA and is associated with cardiac or neurological conditions. It may also be idiopathic. Hypoventilation associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or chronic neuromuscular conditions may also interfere with sleep quality, causing excessive sleepiness.

Sleep apnoea assessment

Evaluating sleep apnoea includes a clinical assessment of the likelihood of sleep apnoea followed by overnight monitoring (sleep study) to identify sleep apnoea and its severity, as well as assessing sleepiness based on subjective and sometimes objective tools.

Clinical and physical features12,16

Clinical features can have a high predictive value for a subsequent diagnosis of OSA via a sleep study. Criteria of significant concern include:

- BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2

- BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2 and either

- hypertension requiring ≥ 2 medications for control, or

- type 2 diabetes

- sleepiness-related crash or accident, off- road deviation, or rear-ending another vehicle by report or observation

- excessive sleepiness during the major wake period.

Other clinical features include:

- habitual snoring during sleep

- witnessed apnoeic events (often in bed by a spouse/partner) or falling asleep inappropriately (particularly during non- stimulating activities such as watching television, sitting reading, travelling in a car, when talking with someone)

- feeling tired despite adequate time in bed.

Poor memory and concentration, morning headaches and insomnia may also be presenting features. The condition is more common in men and with increasing age. Other physical features commonly include a thick neck (>42 cm in men, >41 cm in women) and a narrow oedematous (‘crowded’) oropharynx. The presence of type 2 diabetes and difficult- to-control high blood pressure should also increase the suspicion of sleep apnoea. However, the condition may be present without these features.

The STOP-BANG, OSA-50, and Berlin Questionnaire are clinical screening tools with demonstrated predictive value for subsequent diagnosis of sleep apnoea. Using these questionnaires may assist in the decision to refer for further sleep studies. For general guidance on sleep studies, refer to relevant best practice guidelines (e.g. Australasian Sleep Association’s Guidelines for sleep studies in adults,17 available at www.sleep.org.au).

Sleep studies, referral and management17,18

People in whom sleep apnoea, chronic excessive sleepiness or another medical sleep disorder is suspected should be referred to a specialist sleep physician for further assessment, investigation with overnight polysomnography (either in the laboratory or home) and management. Home sleep studies are widely available with Medicare reimbursed direct referrals offered for patients who have a high score on sleep apnoea and daytime sleepiness screening questionnaires (e.g. ≥ 3 on STOP- Bang and Epworth Sleepiness Scale score ≥ 8).

Referral to a sleep specialist should also be considered for any person who has unexplained daytime sleepiness while driving, or who has been involved in a motor vehicle crash that may have been caused by sleepiness.

Non-driving or restricted driving periods can be considered while assessing the response to treatment and may be determined on a case-by-case basis. Examples of restrictions that can be considered include limiting driving duration (e.g. from 30 minutes with graduated increasing times) or no night driving (11PM– 7AM). For commercial vehicle drivers, this is assessed by a sleep specialist considering the improvement in sleepiness and the related driving risk. The efficacy of treatment should be documented with:

- minimal adherence to treatment

- effectiveness of treatment

- resolution of sleepiness.

A person found to be positive for moderate to severe OSA on polysomnography, but who denies symptoms and declines treatment, may be offered a Maintenance of Wakefulness Test (MWT) (the MWT should include a drug screen and apply a 40-minute protocol). For those with a normal MWT, the driver licensing authority may consider a conditional licence without OSA treatment subject to review in one year.

Subjective measures of sleepiness19, 20, 21

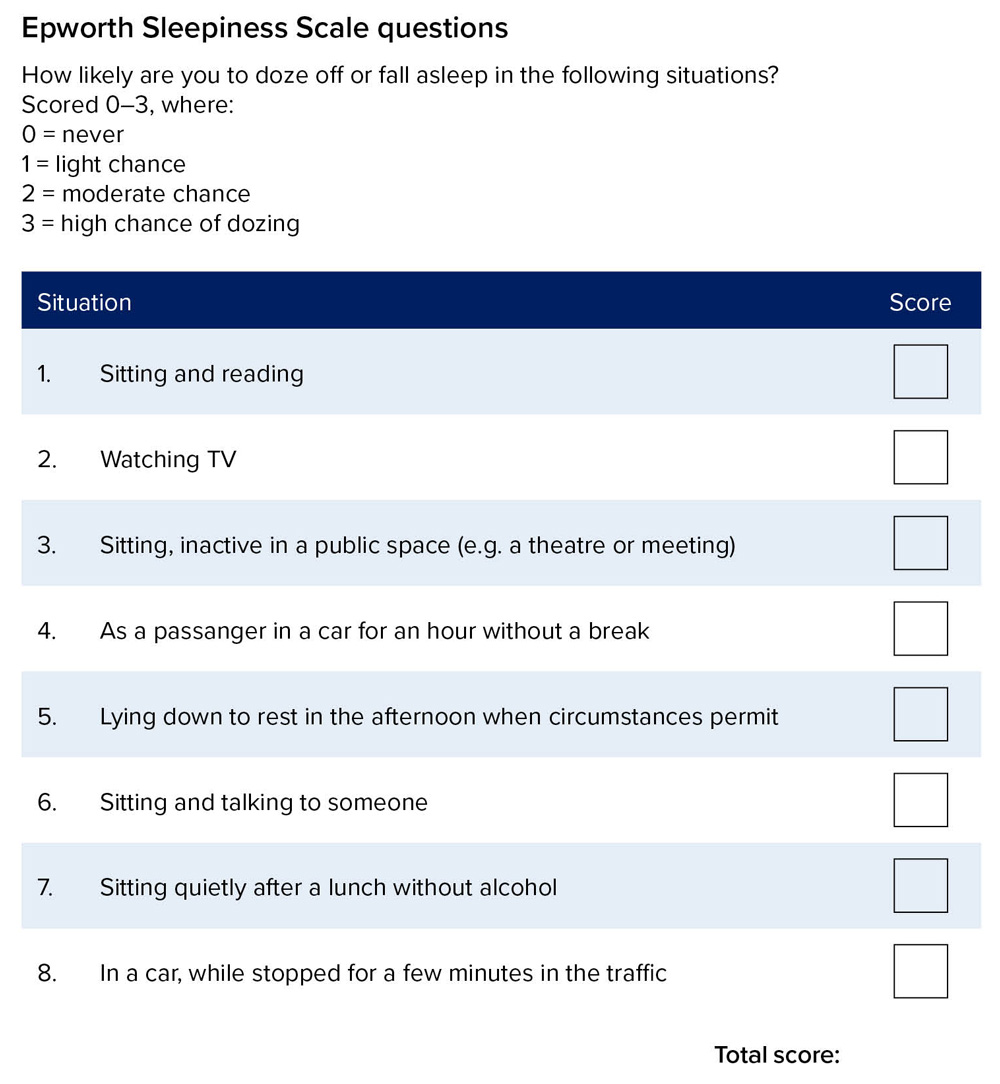

Determining excessive daytime sleepiness is a clinical decision, which may be assisted with clinical tools. Tools such as the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) or other validated questionnaires can be used as subjective measures of excessive daytime sleepiness while recognising that the ESS is neither sensitive nor specific in the diagnosis of OSA. Such tests rely on honest completion by the driver, and there is evidence that incorrect reporting may occur in some cases. The tools are therefore just one aspect of the comprehensive assessment.

The responses to eight questions for the ESS (refer to Figure 15. Epworth Sleepiness Scale questions) relating to the likelihood of falling asleep in certain situations are scored and summed. A score of 0–10 is within the normal range, 11–15 indicates mild-moderate daytime sleepiness, and a score of 16–24 indicates moderate to severe excessive daytime sleepiness and may be associated with an increased risk of motor vehicle crashes.

A history of frequent self-reported sleepiness while driving or motor vehicle crashes caused by sleepiness also indicates a high risk of motor vehicle crashes.

Figure 15: Epworth Sleepiness Scale questions

* The Epworth Sleepiness Scale is under copyright to Dr Murray Johns 1991–1997.

It may be used by individual doctors without permission, but its use on a commercial basis must be negotiated.

Download Figure 15 | PDF

Objective measures of sleepiness22

Objective measures include the MWT. Excessive sleepiness on the MWT suggests impaired driving performance.

Screening tools that combine questions and physical measurements (e.g. the Multivariate Apnoea Prediction Questionnaire) have been evaluated for screening people for sleep disorders in a clinical setting. Their efficacy for screening large general populations remains under evaluation.

Commercial vehicle drivers

Commercial vehicle drivers who are diagnosed with sleep apnoea and require treatment must have an annual review by a sleep specialist to ensure adequate treatment is maintained. For drivers who are treated with CPAP, it is recommended that they use CPAP machines with a usage meter to allow objective assessment and recording of treatment compliance. Minimally acceptable adherence with treatment is defined as four hours or more per day of use on 70 per cent or more of days. An assessment of sleepiness should be made, and an objective measurement of sleepiness should be considered (MWT), particularly if there is a concern about persisting sleepiness or treatment compliance.

8.2.4 Narcolepsy

Narcolepsy is present in 0.05 per cent of the population and usually starts in the second or third decade of life. Sufferers present with excessive sleepiness and can have periods of sleep with little or no warning of sleep onset. Other symptoms include cataplexy, sleep paralysis and vivid hypnagogic hallucinations. Inadequate warning of oncoming sleep and cataplexy put drivers at high risk.

There is a subgroup of people who are excessively sleepy but do not have all the diagnostic features of narcolepsy. In addition, some people may have other central disorders of hypersomnolence such as idiopathic hypersomnia. For drivers with idiopathic hypersomnia or sleepiness due to other central disorders of hypersomnolence, refer to the medical standards for Sleep apnoea syndrome, excessive sleepiness, and other sleep disorders .

Diagnosis of narcolepsy is made on the combination of clinical features. A multiple sleep latency test (MSLT) is conducted, with a diagnostic sleep study on the prior night to exclude other sleep disorders and aid interpretation of the MSLT.

Drivers suspected of having narcolepsy should be referred to a sleep specialist or neurologist for assessment (including an MSLT) and management.

Sleepiness in narcolepsy can usually be managed effectively with scheduled naps and stimulant medication. Additional treatment for cataplexy may be required. Commercial vehicle drivers on a conditional licence should have a review at least annually by their specialist.

8.2.5 Advice to patients

All patients suspected of having sleep apnoea or other sleep disorders should be warned about the potential effect on road safety.

General advice may include:

- minimising unnecessary driving

- minimising driving at times when they would normally be asleep

- allowing adequate time for sleep and avoiding driving after having missed a large portion of their normal sleep

- avoiding alcohol and sedative medications

- avoiding using over-the-counter or other non-prescribed substances for maintaining wakefulness

- ensuring prescribed treatments are taken as required

- resting and limiting driving if they are sleepy

- heeding the advice of a passenger that the driver is dozing off.

It is the responsibility of the driver to avoid driving if they are sleepy, comply with treatment, maintain their treatment device, attend review appointments and honestly report their condition to their treating physician.