2.2 General assessment and management guidelines

In this section

2.2.2. Ischaemic heart disease

2.2.4. Cardiac surgery (open chest)

2.2.5. Disorders of rate, rhythm or conduction

2.2.6. Implantable cardioverter defibrillators

2.2.8. Long-term anticoagulant therapy

2.2.9. Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism

2.2.11. Ventricular assist devices

From 22 June 2022 there have been changes to the fitness to drive criteria for the following conditions:

- Implantable cardioverter defibrillator (commercial vehicle drivers)

- Ventricular assist devices (private vehicle drivers)

- Congenital disorders (private and commercial vehicle drivers)

See summary of changes and download the fact sheet for more details.

2.2.1 Non-driving periods

A number of cardiovascular incidents and procedures affect short-term driving capacity as well as long-term licensing status – for example, acute myocardial infarction and cardiac surgery. Such situations present an obvious driving risk that cannot be addressed by the licensing process in the short term. The person should be advised not to drive for the appropriate period, as shown in Table 5. Suggested non- driving periods after cardiovascular events or procedures.

The variation in non-driving periods reflects the varying effects of these conditions and is based on expert opinion. These non-driving periods are minimum advisory periods only and are not enforceable by the licensing process. The recommendations regarding long-term licence status (including conditional licences) should be considered once the condition has stabilised and driving capacity can be assessed as per the licensing standards outlined in this chapter.

Table 5: Suggested non-driving periods after cardiovascular events or procedures

| Event/procedure | Minimum non-driving period (advisory) – private vehicle drivers | Minimum non-driving period (advisory) – commercial vehicle drivers |

|---|---|---|

| Ischaemic heart disease | ||

| Acute myocardial infarction | 2 weeks | 4 weeks |

| Percutaneous coronary intervention – for example, for angioplasty | 2 days | 4 weeks |

| Coronary artery bypass grafts | 4 weeks | 3 months |

| Disorders of rate, rhythm and conduction | ||

| Cardiac arrest | 6 months | 6 months |

| Implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) insertion | 6 months after cardiac arrest | 6 months for primary prevention Not applicable for secondary prevention |

| Generator change of an ICD | 2 weeks | 2 weeks for primary prevention Not applicable for secondary prevention |

| ICD therapy associated with symptoms of haemodynamic compromise | 4 weeks | Not applicable |

| Cardiac pacemaker insertion | 2 weeks | 4 weeks |

| Vascular disease | ||

| Aneurysm repair | 4 weeks | 3 months |

| Valvular replacement (including treatment with MitraClips and transcutaneous aortic valve replacement) | 4 weeks | 3 months |

| Other | ||

| Deep vein thrombosis | 2 weeks | 2 weeks |

| Heart/lung transplant | 6 weeks | 3 months |

| Ventricular assist device | 3 months | Not applicable |

| Pulmonary embolism | 6 weeks | 6 weeks |

| Syncope (due to cardiovascular causes) | 4 weeks | 3 months |

2.2.2 Ischaemic heart disease

In people with ischaemic heart disease, the severity rather than the mere presence of ischaemic heart disease should be the primary consideration in assessing fitness to drive.

Health professionals should consider any symptoms of sufficient severity to be a risk while driving. Those who have had a previous myocardial infarction or similar event are at greater risk of recurrence than the normal population, so cardiac history is an important consideration. An electrocardiogram (ECG) should be performed if clinically indicated.

Exercise testing

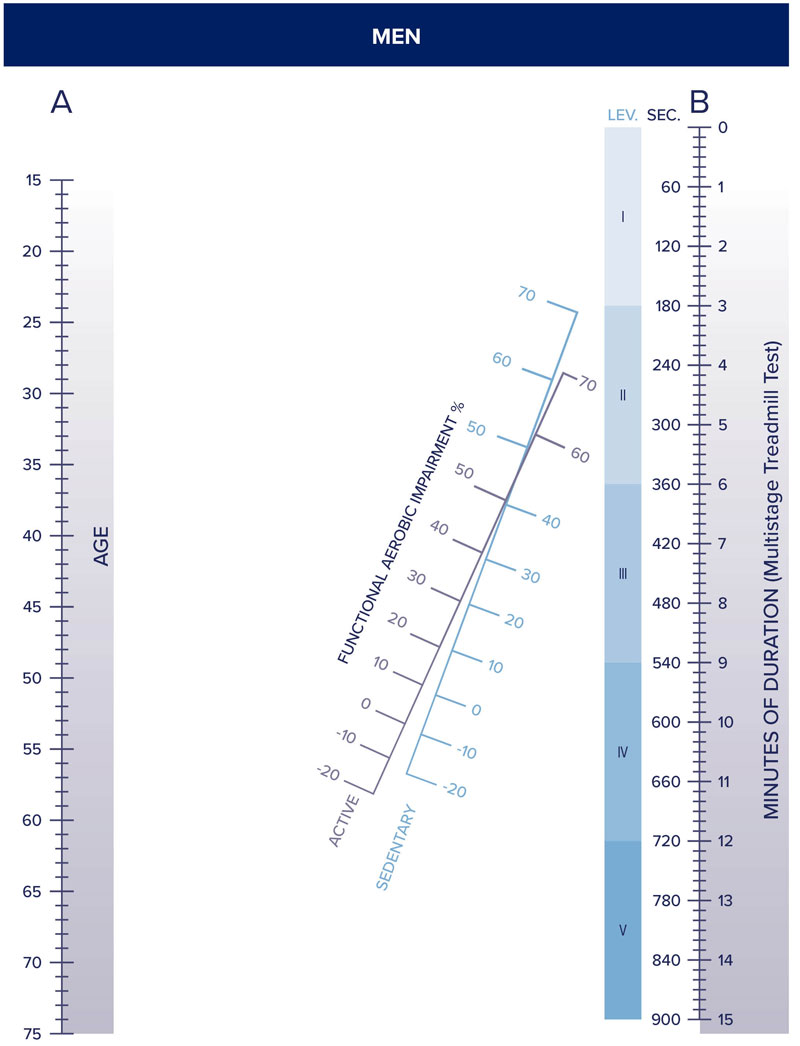

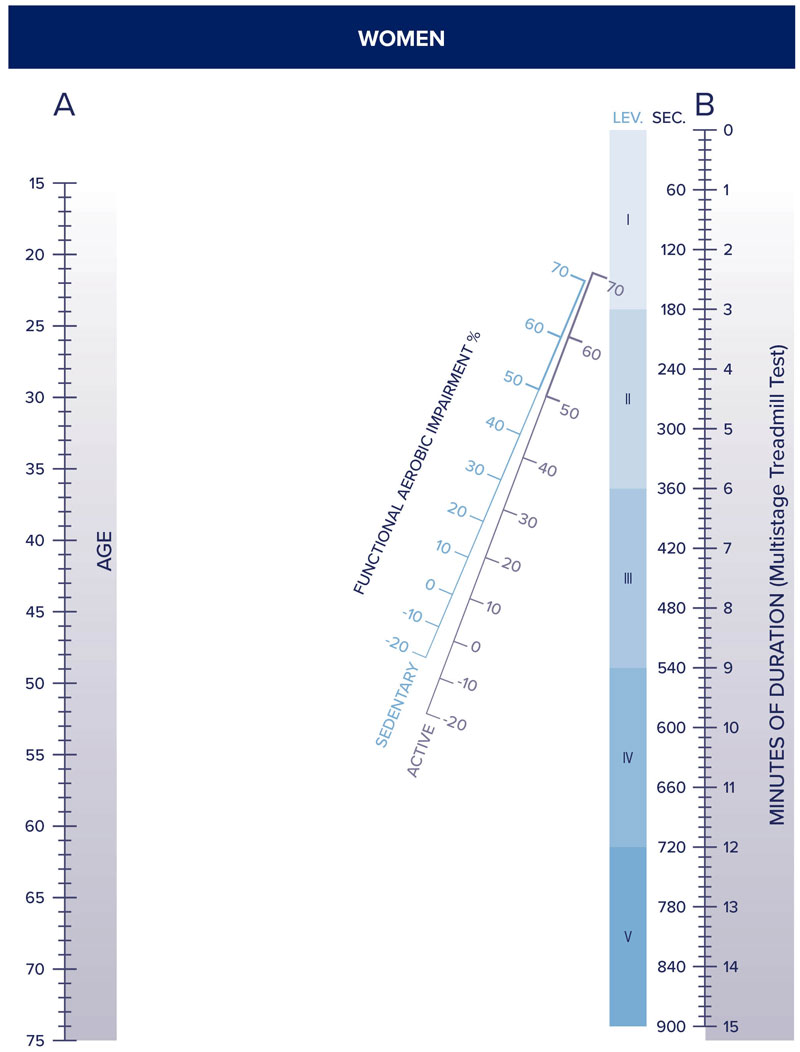

The Bruce protocol or equivalent is recommended for formal exercise testing. Where a patient is not capable of performing a treadmill test due to a medical condition, for example osteoarthritis of the knee, an equivalent stress test may be used. Nomograms for assessing functional capacity are shown in Figure 7 and Figure 8.

Suspected angina pectoris

Where chest pains of uncertain origin are reported, every attempt should be made to reach a diagnosis. In the meantime, the person should be advised to restrict their driving until their licence status is determined, particularly in the case of commercial vehicle drivers. If the tests are positive or the person remains symptomatic and requires antianginal medication to control symptoms, the requirements listed for proven angina pectoris apply.

Risk factors

Multiple risk factors interact in the development of ischaemic heart disease and stroke. These factors include age, gender, blood pressure, smoking, total cholesterol:HDL ratio, diabetes and ECG evidence of left ventricular hypertrophy. The combined effect of these factors on risk of cardiovascular disease may be calculated using the Australian Cardiovascular Risk Charts (an electronic calculator is available at www.cvdcheck.org.auOpens in new window).

Routine screening for these risk factors is not required for licensing purposes, except where specified for certain commercial vehicle drivers as part of their additional accreditation or endorsement requirements. However, when a risk factor such as high blood pressure is being managed, it is good practice to assess other risk factors and to calculate overall risk. This risk assessment may be helpful additional information in determining fitness to drive, especially for commercial vehicle drivers (refer also to section 2.2.3. High blood pressure).

Figure 7: Bruce protocol nomogram for men

© Robert Bruce, M.D. Dept. of Cardiology School of Medicine University of Washington

Reproduced with permission Department of Cardiology, School of Medicine, University of Washington.

Figure 8: Bruce protocol nomogram for women

© Robert Bruce, M.D. Dept. of Cardiology School of Medicine University of Washington

Reproduced with permission Department of Cardiology, School of Medicine, University of Washington.

2.2.3 High blood pressure

The cut-off blood pressure values at which a person is considered unfit to hold an unconditional licence do not reflect usual goals for managing hypertension. Rather, they reflect levels that are likely to be associated with sudden incapacity due to neurological events (e.g. stroke). The cut-off points are based on expert opinion.

It is a general requirement that conditional licences for commercial vehicle drivers are issued by the driver licensing authority based on the advice of an appropriate medical specialist and that these drivers are reviewed periodically by the specialist to determine their ongoing fitness to drive (refer to Part A section 4.4. Conditional licences). In the case of high blood pressure, ongoing fitness to drive may be assessed by the treating general practitioner, provided this is mutually agreed by the specialist and the general practitioner. The initial recommendation of a conditional licence must, however, be based on the opinion of the specialist.

2.2.4 Cardiac surgery (open chest)

Cardiac surgery may be performed for various reasons including valve replacement, excision of atrial myxoma and correction of septal defects. In some cases this is curative of the underlying disorder and so will not affect licence status for private or commercial vehicle drivers (refer also to Table 5. Suggested non-driving periods after cardiovascular events or procedures). In other cases, the condition may not be stabilised, and the effect on driving safety and hence on licence status needs to be individually assessed. All cardiac surgery patients should be advised regarding safety of driving in the short term as for any other post-surgery patient (e.g. taking into account the limitation of chest and shoulder movements after sternotomy).

2.2.5 Disorders of rate, rhythm or conduction

People with recurrent arrhythmias causing syncope or pre-syncope are usually not fit to drive. A conditional licence may be considered after appropriate treatment and an event-free non-driving period (refer to Table 5. Suggested non-driving periods after cardiovascular events or procedures).

2.2.6 Implantable cardioverter defibrillators

People fitted with an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) have a risk of sudden incapacity, which poses a crash risk. The risk is mainly a consequence of the underlying condition; however, there is also a risk of inappropriate discharge of the device (i.e. when there is no ventricular arrhythmia). This risk is considered unacceptable for commercial vehicle drivers to hold an unconditional licence. A conditional commercial licence may be considered by the driver licensing authority on the advice of a specialist in electrophysiology based on the nature of the driving tasks and criteria outlined in the medical standards table when the device is inserted for primary prevention. A person is not fit to hold a conditional commercial licence when the ICD is inserted for secondary prevention.

2.2.7 Aneurysms

Thoracic aortic aneurysms are largely asymptomatic until a sudden and catastrophic event occurs, such as rupture or dissection. Such events are rapidly fatal in a large proportion of patients. Risk varies with the type and size of aneurysm. The standard is set more stringently for atherosclerotic aneurysms or aneurysms associated with bicuspid aortic valve, compared with aneurysms associated with genetic aortopathy, including Marfan’s, Turner’s and Ehlers-Danlos syndromes, and familial aortopathy.

See reference 8

2.2.8 Long-term anticoagulant therapy

Long-term anticoagulant therapy may be used to lessen the risk of emboli in disorders of cardiac rhythm, following valve replacement, for deep venous thrombosis and other similar conditions. If not adequately controlled, there is a risk of bleeding that, in the case of an intracranial bleed, may acutely affect driving. People on private vehicle licences may drive without licence restriction and without reporting to the driver licensing authority if the treating doctor considers anticoagulation is maintained at the appropriate level for the underlying condition. Commercial vehicle drivers do not meet the requirements for an unconditional licence and may drive only with a conditional licence.

2.2.9 Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism

While deep vein thrombosis (DVT) may lead to an acute pulmonary embolus (PE), there is little evidence that such an event causes crashes. Therefore, no standard applies for either DVT or PE, although non-driving periods are advised (refer to Table 5. Suggested non-driving periods after cardiovascular events or procedures). If long-term anticoagulation treatment is prescribed, the standard for anticoagulant therapy should be applied (refer to section 2.2.8 Long-term anticoagulant therapy).

2.2.10 Syncope

If an episode of syncope is vasovagal in nature with a clear-cut precipitating factor (such as venesection), and the situation is unlikely to occur while driving, the person may generally resume driving within 24 hours. With syncope due to other cardiovascular causes, an appropriate non-driving period should be advised (at least four weeks for private vehicle drivers and at least three months for commercial vehicle drivers), after which time their ongoing fitness to drive should be assessed. In cases where it is not possible to determine an episode of loss of consciousness is due to syncope or some other cause, refer to section 1.2.4. Blackouts of undetermined mechanism.

2.2.11 Ventricular assist devices

A ventricular assist device (VAD) is an electromechanical circulatory device used to partially or completely replace the function of a failing heart. Some VADs are intended for short-term use, typically for patients recovering from heart attacks or heart surgery. Others are intended for long-term use (months to years and in some cases for life), typically for heart failure. They carry a small risk of stroke or device failure. The driver licensing authority may consider a conditional licence for a private driver with a LVAD or BiVAD, but not for commercial drivers.

As part of ongoing recovery, patients should undergo a rehabilitation program to ensure confidence in using the equipment.

People with very severe heart failure may have persisting cognitive or neurological impairment and warrant a practical driving assessment (refer to Part A section 2.3.1. Practical driver assessments).

2.2.12 Congenital disorders

The impact of congenital heart disorders on driving safety relates to the effects of the congenital lesion on systemic ventricular function and complicating arrhythmias. Pacemakers and ICDs are employed in the management of some individuals with congenital heart disease. People on private vehicle licences may drive without licence restriction and without reporting to the driver licensing authority if they have uncomplicated congenital heart disease with no or minimal haemodynamic effect (e.g. pulmonary stenosis, atrial septal defect, small ventricular septal defect, bicuspid aortic valve, patent ductus arteriosus or mild coarctation of the aorta), and there are no or minimal symptoms (chest pain, palpitations, breathlessness).

The relevant sections on atrial fibrillation, paroxysmal arrhythmias, implantable cardioverter defibrillators, cardiac pacemaker and heart failure may also apply to drivers with complex congenital heart disease.