3.2 General assessment and management guidelines

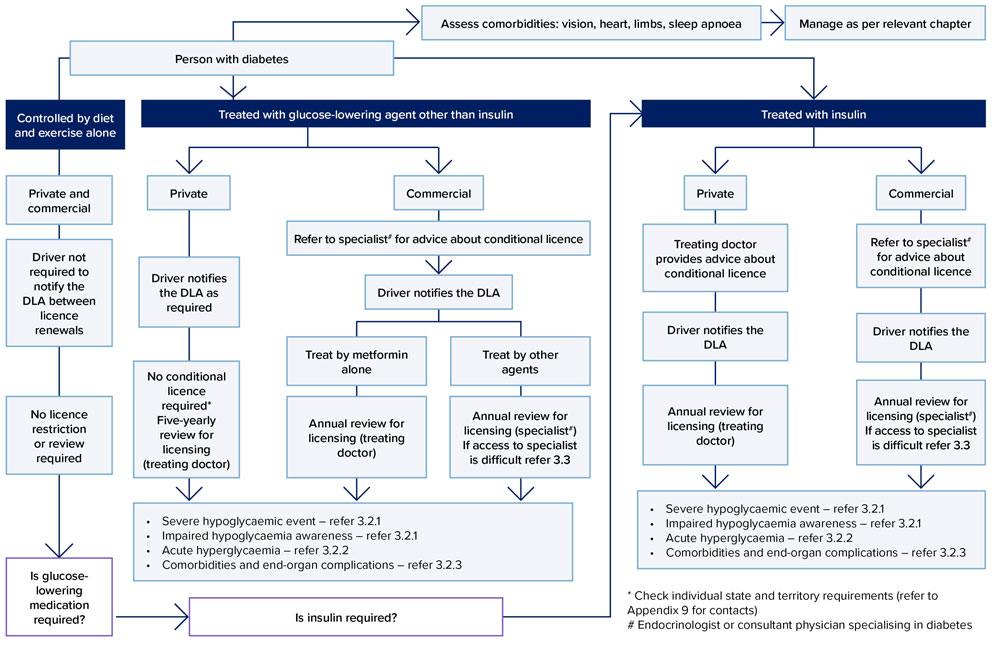

General management of diabetes in relation to fitness to drive is summarised in Figure 10.

Note, for the purpose of the diabetes standard, appropriate specialist means an endocrinologist or consultant physician specialising in diabetes. For general guidance on diabetes management refer to relevant best practice guidelines (e.g. Royal Australasian College of General Practitioners’ Management of type 2 diabetes: a handbook for general practice8 or the National Health and Medical Research Council’s National evidence based clinical care guidelines for type 1 diabetes for children, adolescents and adults9).

3.2.1 Hypoglycaemia

Definition: severe hypoglycaemic event6,8,9

For the purposes of this document, a ‘severe hypoglycaemic event’ is defined as an event of hypoglycaemia of sufficient severity such that the person is unable to treat the hypoglycaemia themselves and so requires someone else to administer treatment. It includes hypoglycaemia causing loss of consciousness or seizure. It can occur during driving or at any other time of the day or night. A severe hypoglycaemic event is particularly relevant to driving because it affects brain function and may cause impairment of perception, motor skills or consciousness. It may also cause abnormal behaviour. A severe hypoglycaemic event is to be distinguished from mild hypoglycaemic events, the latter with symptoms such as sweating, tremulousness, hunger and tingling around the mouth, which are common occurrences in the life of a person with diabetes treated with insulin and some hypoglycaemic agents.

Potential causes7

Hypoglycaemia may be caused by many factors including non-adherence or alteration to medication, unexpected exertion, alcohol intake or irregular meals. Meal regularity and variability in medication administration may be important considerations for long-distance commercial driving or for drivers operating on shifts. Impairment of consciousness and judgement can develop rapidly and result in loss of control of a vehicle. Excessively tight control may contribute to hypoglycaemia.

Advice to drivers

The driver should be advised not to drive if a severe hypoglycaemic event is experienced while driving or at any other time, until they have been cleared to drive by a medical practitioner. The driver should also be advised to take appropriate precautionary steps to help avoid a severe hypoglycaemic event – for example, by:

- complying with general medical review requirements as requested by their general practitioner or specialist

- not driving if either their blood glucose is at or less than 5 mmol/L or if, while wearing a continuous or flash glucose monitor, the predicted glucose level is showing downward trends into the hypoglycaemia range (measured when the vehicle is parked)

- wearing a continuous or flash glucose monitor, preferably with an active hypoglycaemia alert or alarm

- not driving for more than two hours without considering having a snack

- not delaying or missing a main meal

- self-monitoring blood glucose levels before driving and every two hours during a journey, as reasonably practical

- carrying adequate glucose in the vehicle for self-treatment

- treating mild hypoglycaemia if symptoms occur while driving including:

- safely steering the vehicle to the side of the road

- turning off the engine and removing the keys from the ignition

- self-treating the low blood glucose

- checking the blood glucose levels 15 minutes or more after the hypoglycaemia has been treated and ensuring it is above 5 mmol/L

- not recommencing driving until feeling well and until at least 30 minutes after the blood glucose is above 5 mmol/L.

Non-driving period after a ‘severe hypoglycaemic event’

If a severe hypoglycaemic event occurs (as defined in section 3.2.1. Hypoglycaemia), the person should not drive for a significant period of time and will need to be urgently assessed. The minimum period of time before returning to drive is generally six weeks because it often takes many weeks for patterns of glucose control and behaviour to be re-established and for any temporary ‘impaired hypoglycaemia awareness’ to resolve (see below). The non- driving period will depend on factors such as identifying the reason for the episode, the specialist’s opinion and the type of motor vehicle licence. The specialist’s recommendation for returning to driving should be based on the patient’s behaviour and objective measures of glycaemic control (documented blood glucose) over a reasonable interval.

Impaired hypoglycaemic awareness10,11,12,13,14

Impaired hypoglycaemic awareness exists when a person does not regularly sense the usual early warning symptoms of mild hypoglycaemia such as sweating, tremulousness, hunger, tingling around the mouth, palpitations and headache. It markedly increases the risk of a severe hypoglycaemic event occurring and is therefore a risk for road safety. Rates of severe hypoglycaemia may be up to seven times higher compared with those who retain hypoglycaemia awareness. Impaired hypoglycaemia awareness occurs in 20–25 per cent of people with type 1 diabetes and about 10 per cent of those with type 2 diabetes. Prevalence is higher in older people and in those with a longer duration of diabetes.

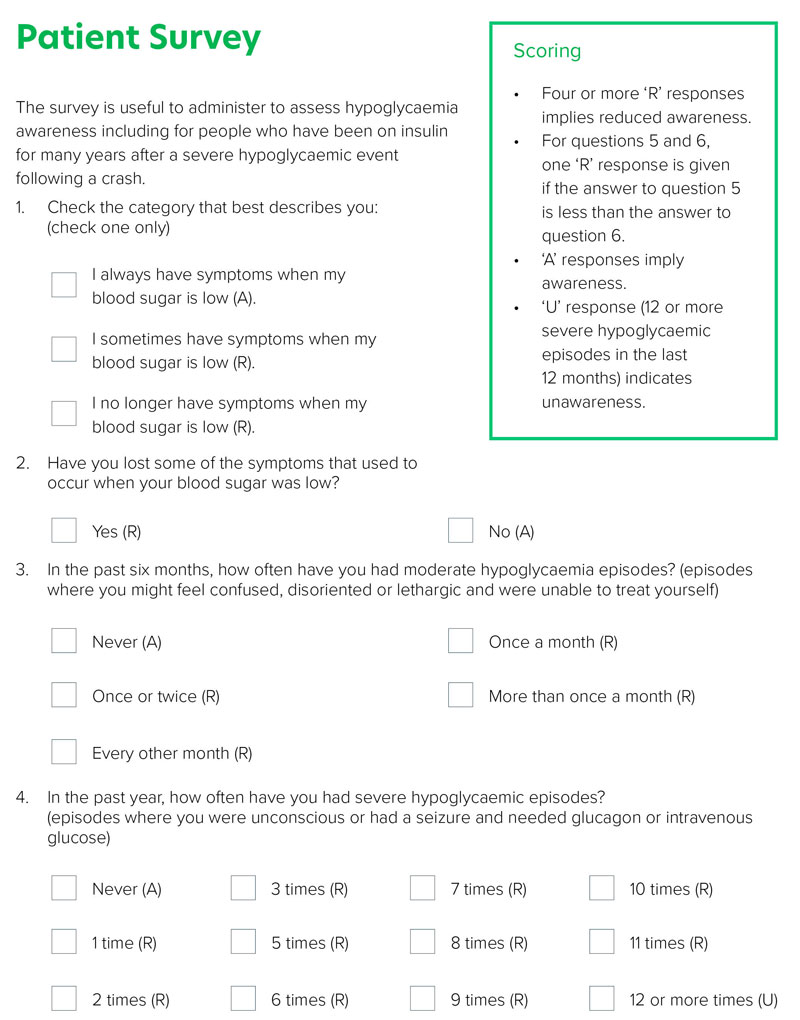

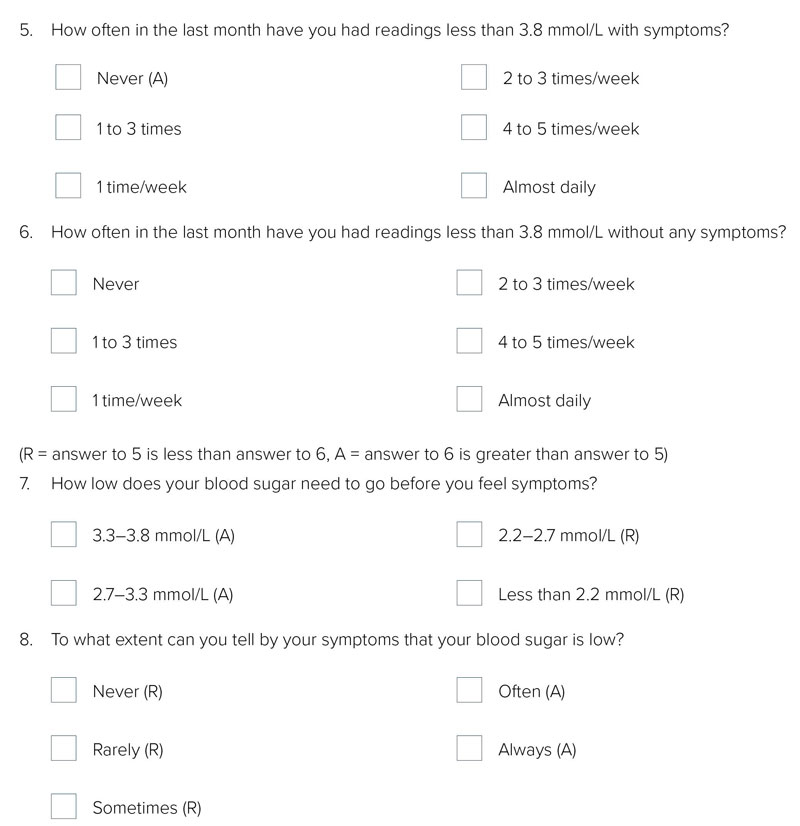

Impaired hypoglycaemic awareness may be screened for using the Clarke questionnaire (refer to Figure 9. Clarke hypoglycaemia awareness survey), which may be particularly useful for people with insulin-treated diabetes of longer duration (more than 10 years), or following a severe hypoglycaemic event or after a crash. The use of devices such as continuous or flash glucose monitors do not replace the need for a person to be able to sense the warning signs of hypoglycaemia or to compensate for impaired hypoglycaemia awareness.

When impaired hypoglycaemia awareness develops in a person who has experienced a severe hypoglycaemic event, it may improve in the subsequent weeks and months if further hypoglycaemia can be avoided.

A person with persistent impaired hypoglycaemia awareness should be under the regular care of a medical practitioner with expert knowledge in managing diabetes (e.g. an endocrinologist or diabetes specialist), who should be involved in assessing their fitness to drive. As reflected in the standards table, any driver who has a persistent impaired hypoglycaemia awareness is generally not fit to drive unless their ability to experience early warning symptoms returns or they have an effective management strategy for lack of early warning symptoms. For private drivers, a conditional licence may be considered by the driver licensing authority, taking into account the opinion of an appropriate specialist, the nature and extent of the driving involved and the driver’s self-care behaviours.

In managing impaired hypoglycaemia awareness, the medical practitioner should focus on aspects of the person’s self-care to minimise a severe hypoglycaemic event occurring while driving, including steps described above (Advice to drivers). In addition, self-care behaviours that help to minimise severe hypoglycaemic events in general should be a major ongoing focus of regular diabetes care. This requires attention by both the medical practitioner and the person with diabetes to diet and exercise approaches, insulin regimens and blood glucose testing protocols.

Figure 9: Clarke hypoglycaemia awareness survey

Note: Units of measure have been converted from mg/dl to mmol/L as per http://www.onlineconversion.com/blood_sugar.htm

3.2.2 Acute hyperglycaemia

While acute hyperglycaemia may affect some aspects of brain function, there is not enough evidence to determine the regular effects on driving performance and related crash risk. Each person with diabetes should be counselled about managing their diabetes during days when they are unwell and should be advised not to drive if they are acutely unwell with metabolically unstable diabetes.

3.2.3 Comorbidities and end-organ complications

Assessment and management of comorbidities is an important aspect of managing people with diabetes with respect to their fitness to drive.

This should be part of routine review as per recommended practice and may include, but is not limited to, the following.

Vision

Refer to section 10. Vision and eye disorders. Visual acuity should be tested annually. Retinal screening should be undertaken every second year if there is no retinopathy, or more frequently if at high risk. Visual field testing is not required unless clinically indicated.7,8

Neuropathy and foot care

While it can be difficult to be prescriptive about neuropathy in the context of driving, it is important that the severity of the condition is assessed. Adequate sensation and movement for the operation of foot controls is required (refer to section 6. Neurological conditions and section 5. Musculoskeletal conditions).

Sleep apnoea

Sleep apnoea is a common comorbidity affecting many people with type 2 diabetes and has substantial implications for road safety. The treating health professional should be alert to potential signs (e.g. BMI greater than 35) and symptoms, and apply the Epworth Sleepiness Scale as appropriate (refer to section 8. Sleep disorders).

Cardiovascular

There are no diabetes-specific medical standards for cardiovascular risk factors and driver licensing. Consistent with good medical practice, people with diabetes should have their cardiovascular risk factors periodically assessed and treated as required (refer to section 2. Cardiovascular conditions).

3.2.4 Gestational diabetes mellitus

The standards in this chapter apply to diabetes mellitus as a chronic condition. The self-limiting condition known as gestational diabetes mellitus does not affect licensing. However, consideration should be given to short-term fitness to drive in women with gestational diabetes mellitus treated with insulin, although severe hypoglycaemia in this condition is rare. Affected women should be counselled to recognise symptoms and to restrict driving when symptoms occur.

Figure 10: Management of diabetes and driving